The “Red Clause”

Lately I’ve been reading Samuel Hopkins Adams’ investigative journalism piece The Great American Fraud (serialized in Collier’s, 1905–1906). Adams inveighs against the scourge of “patent medicines” that were in most cases neither patented, nor medicines, but rather delivery vehicles for alcohol or worse.

In some respects it seems to have been a simpler time:

In many places samples of headache powders are distributed on the doorsteps. The St. Louis Chronicle records a result:

Huntington, W.Va., Aug. 15, 1905. — While Mrs. Thomas Patterson was preparing supper last evening she was stricken with a violent headache and took a headache powder that had been thrown in at her door the day before. Immediately she was seized with spasms, and in an hour she was dead.

But in other respects, the prevalent attitudes were extremely modern:

With a few honorable exceptions, the press of the United States is at the beck and call of the patent medicines. Not only do the newspapers modify news possibly affecting these interests, but they sometimes become their active agents.

F.J. Cheney, proprietor of Hall’s Catarrh Cure, devised some years ago a method of making the press do his fighting against legislation compelling makers of remedies to publish their formulae, or to print on the labels the dangerous drugs contained in the medicine[.] This scheme he unfolded at a meeting of the Proprietary Association of America, of which he is now president. He explained that he printed in red letters on every advertising contract a clause providing that the contract should become void in the event of hostile legislation, and he boasted how he had used this as a club in a case where an Illinois legislator had, as he put it, attempted to hold him for three hundred dollars on a strike bill.

“I thought I had a better plan than this,” said Mr. Cheney to his associates, “so I wrote to about forty papers and merely said: ‘Please look at your contract with me and take note that if this law passes you and I must stop doing business.’ The next week, every one of them had an article, and Mr. Man had to go.”

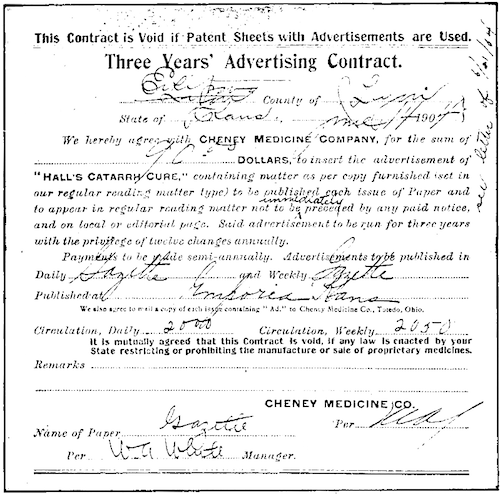

So emphatically did this device recommend itself to the assemblage that many of the large firms took up the plan, and now the “red clause” is a familiar device in the trade. [Here is] a contract between Mr. Cheney’s firm and the Emporia Gazette, William Allen White’s paper[: “It is mutually agreed that this Contract is void, if any law is enacted by your State restricting or prohibiting the manufacture or sale of proprietary medicines.”]

Emboldened by this easy coercion of the press, certain firms have since used the newspapers as a weapon against “price-cutting,” by forcing them to refuse advertising of the stores which reduce rates on patent medicines. Tyrannical masters, these heavy purchasers of advertising space!

To what length daily journalism will go at the instance of the business office was shown in the great advertising campaign of Paine’s Celery Compound, some years ago. The nostrum’s agent called at the office of a prominent Chicago newspaper and spread before its advertising manager a full-page advertisement, with blank spaces in the center.

“We want some good, strong testimonials to fill out with,” he said.

“You can get all of those you want, can’t you?” asked the newspaper manager.

“Can you?” returned the other. “Show me four or five strong ones from local politicians and you get the ad.”

[…]

Should the newspapers, the magazines and the medical journals refuse their pages to this class of advertisements, the patent-medicine business in five years would be as scandalously historic as the South Sea Bubble, and the nation would be the richer not only in lives and money, but in drunkards and drug-fiends saved.