Rolling 2d6 with playing cards

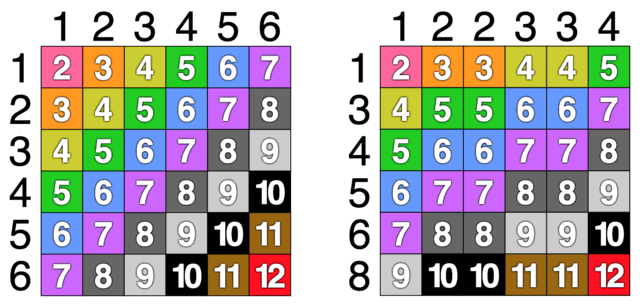

Last night Alexandre Muñiz gave a Celebration of Mind talk titled “How to Roll Two Dice.” If you want to roll 2d6, you can do it either the boring way (by rolling two ordinary d6s) or the interesting way — by rolling two distinct d6s, one labeled 1-2-2-3-3-4 and the other labeled 1-3-4-5-6-8. These Sicherman dice (invented by George Sicherman and first reported by Martin Gardner in 1978) produce the same distribution of 36 possible results as the ordinary 2d6:

(Image modified from Cmglee on Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0.)

I admit that some of the rest of the talk went over my head — or at least went mathy so fast I lost track of what our goal was. However, at one point Alexandre mentioned a really cool puzzle, which seems to have first appeared on the Internet in March 2007 as part of a random Metafilter thread about Monopoly. User “iconjack” wrote:

The other day I found myself playing Monopoly with Donald Knuth and John Conway. We got the board set up and the money distributed, then realized we were missing the dice.

“The kids must’ve lost the dice,” I apologized.

“That’s okay,” said Dr. Conway. “Do you have any playing cards?”

I went back to the game shelf and retrieved a rather ratty looking deck of cards.

“Yeah, but it looks like about half are missing, including most of the lower-numbered cards.”

I figured he planned on pulling out two sets of ace through six, using them a substitutes for the missing dice.

“But for what it’s worth, here you go,” I said, and handed him the depleted deck.

Dr. Conway quickly flipped through the cards, removing a handful and setting them aside. “It looks like all the hearts are gone,” he said, “and even the other suits are incomplete. But I believe we have all the cards we need.”

He handed me a set of nine cards, explaining “Instead of rolling dice, we’ll simply remove a pair of cards from the nine at random. The roll will be the average of the two cards, where ace through ten assume their usual pip value, a jack is eleven, a queen twelve, and a king thirteen, as one might expect. With the cards I’ve chosen, the distribution will be the same as with a pair of ordinary dice.”

I was intrigued, and impressed, but thought I noticed a flaw in his system, as I handed the cards to Dr. Knuth.

“What about doubles?” I asked. “For Monopoly, we’ll need to know when someone has rolled doubles.”

“Not a problem,” Knuth chimed in, after a brief look at the cards. “If the roll is even and the chosen cards are both diamonds, then doubles have been thrown, so to speak.”

“Fascinating,” I thought. And we then proceeded to play a nice game of Monopoly, which I won easily.

What were the nine cards Dr. Conway pulled from the deck?

Spoiler below the break.

Alexandre has a blog at puzzlezapper.com with more mathy puzzles and games, dice-related and otherwise.

Speaking of doubles, you might have noticed from the tables above that there are only 4 ways to roll doubles on the Sicherman dice (a 1-in-9 chance), as opposed to the 1-in-6 chance of rolling doubles on an ordinary 2d6.

And bouncing around Wikipedia articles on dice, today I learned that in 1848 someone discovered a pair of Etruscan dice where the six sides were (weirdly) inscribed with the spellings of Etruscan number-words, rather than just pips or whatever; and these dice provided important evidence for the names of the numbers 1 through 6 in the Etruscan language. However, the mapping from names to numbers can’t be determined except from other philological evidence. Whatever joker crafted these dice seems to have avoided the now-standard scheme where opposing faces sum to 7; possibly just so that modern linguists would have some problematic evidence to argue about.

SPOILER: Metafilter user “TypographicalError” gives an excellent writeup in that same thread.

Since there are 36 ways to roll two dice, and 36 ways to choose 2 cards out of 9, the number of pairs of cards giving some certain average is the same as the number of dice that do. Specifically, there must be a unique pair giving 12.

There are only two ways to get 12: KJ or QQ. Further, since we know that 12 is automatically a double, we can’t have QQ, as we don’t have two Q♢. So, we know that we have exactly one K, and one J. A similar argument shows that we have exactly one A and one 3.

Now, we have four “odd” cards - if we had any even cards, then the average of the two would not be an integer, which is bad. Therefore we just need to determine how many fives, sevens, and nines we have. To get the two 11 rolls we need, we’ll have to have two nines. Similarly, to get two 3 rolls, we need two fives. Since we know we have 9 cards, there must be exactly one 7, since that’s the only thing left.

Now we need to determine suits. We already know the A, 3, J, K must be diamonds, because rolls of 2 and 12 are automatically doubles. These four cover the double rolls for 2, 6, 8, and 12. If one of the 5s is a diamond, then 5♢J♢ gives a second double 8, which is a problem. Similarly, if one of the 9s is a diamond, then we get an extra double 6. Thus, the 7 is a diamond, since we need another diamond and it’s the only thing left.

Since we’re missing all the hearts, and the 5s and 9s can’t be diamonds, they must be the clubs and spades.

Solution: ♣59 ♢A37JK ♠59