Kafka, math jokes, triangle dissection

The other week, I attended a book club on Kafka’s short story The Burrow. It’s a quite frankly brilliant portrayal of neuroticism. The titular burrow reads like a metaphor for so many things at once: a house, a body of work, a life history. The story (translated by Willa and Edwin Muir) is quotable and yet, somehow, no pull quote could be satisfactory; all I can recommend is that you go read it!

If you’ve read the traditional Kafka repertoire (The Metamorphosis, The Trial, Before the Law, and so on), you might like to know that Kafka himself once boiled down that entire genre into seven sentences:

It was very early in the morning, the streets clean and deserted. I was walking to the station. As I compared the tower clock with my watch I realized that it was already much later than I had thought, I had to hurry, the shock of this discovery made me unsure of the way, I did not yet know my way very well in this town. Luckily, a policeman was nearby; I ran up to him and breathlessly asked him the way. He smiled and said: “From me you want to know the way?”

“Yes,” I said, “since I cannot find it myself.”

“Give it up! Give it up,” he said, and turned away with a sudden jerk, like people who want to be alone with their laughter.

This past Monday I attended Des MacHale’s CoM talk on mathematical jokes and riddles. He recited dozens of his favorites. Some were classics I’d heard before (What’s purple and commutes? An Abelian grape); some were new to me. Apropos of the famous story about Hardy and Ramanujan:

“What was your taxicab number?”

“Oh, some uninteresting number… fourteen, I think.”

“What do you mean ‘uninteresting’? It’s the smallest number that’s the product of 2 and 7 in two different ways.”

I suppose that joke is only one lot over from the ground trodden by Douglas Hofstadter’s fictional mathematiciant Di of Antus, who wrote:

The equation \(n^a + n^b = n^c\) has solutions in positive integers \(a\), \(b\), \(c\), and \(n\) only when \(n = 2\) (and then there are infinitely many triplets \(a\), \(b\), \(c\) which satisfy the equation); but there are no solutions for \(n > 2\). I have discovered a truly marvelous proof of this statement, which, unfortunately, is so small that it would be well-nigh invisible if written in the margin.

And a mathematical riddle: In this sequence of numbers, which one doesn’t belong?

\[11, 13, 16, 17, 21, 24, 29, 32\]The answer, of course, is 24; all the others come with fried rice.

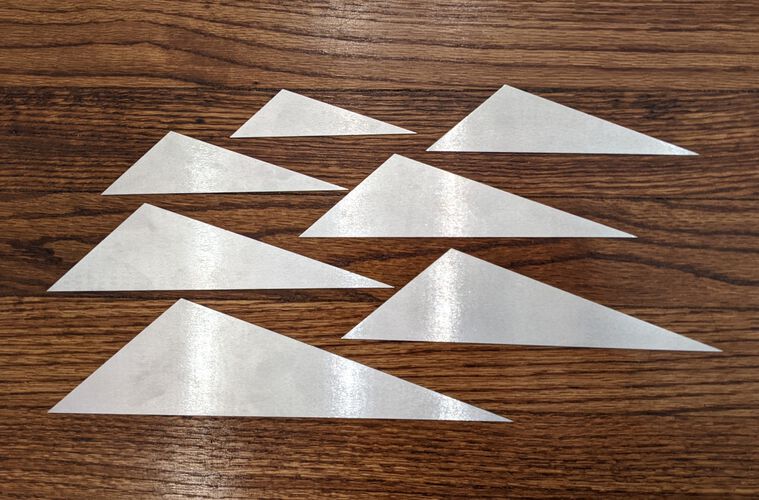

In last month’s CoM talk, Jessica Sklar was talking about dissections of the equilateral triangle into smaller equilateral triangles, and I ended up googling dissections of the equilateral triangle into other things. According to “A note on perfect dissections of an equilateral triangle” (Andrzej Żak, 2009), it turns out that there’s exactly(?) one way to dissect an equilateral triangle into seven similar scalene triangles. The diagram in Żak’s paper didn’t quite satisfy me, and I didn’t have construction paper handy, so I took a few hours and ordered some custom-cut aluminum triangles from Ponoko.com to play around with.

|

|

I have only good things to say about Ponoko. You upload an image (such as this SVG image of seven similar triangles), choose the material and tell them how big you want it (make sure the smallest dimension of each piece is at least one inch if you want them to deburr it for you), and they do the rest! Totally worth it.

Interestingly, although you can dissect an equilateral triangle into (no fewer than) seven similar triangles, simultaneously you cannot dissect any triangle into seven congruent triangular tiles! See “No triangle can be cut into seven congruent triangles” (Michael Beeson, 2010).