My muscle-memory git toolbox

git toolboxThis blog post has been on my to-do list ever since I saw Daniel Stenberg’s blog post “This is how I git” (November 2020). I thought, “I should do one of those posts, too!”

This post focuses on my basic muscle-memory git commands. There are at least two other

major Git subtopics this post doesn’t mention at all: “branching discipline” (what is a release branch?

what’s the difference between rebase and merge?) and “hygiene” (how big should a commit be? what does a good commit message

look like?). That is — as usual for this blog — we’re talking tactics, not strategy.

My workflow (both strategically and tactically) has been pretty stable for a long time. In 2023 it’s the same as it was in 2020; and in 2020 it was recognizably the same as it was in 2016 when I designed my one-hour training session titled “How to git.” (The slides are public here; if you want a live presentation, email me for rates!)

When I started drafting this post in November 2020, I ran a quick history | grep git

to generate a histogram of how often I used each different git command in real life.

I did it again just now — using a more elaborate grep line — and here are the results.

Bear in mind this is on a MacBook where the .bash_history comes haphazardly from only

one Terminal tab at a time. I have no idea

how to search my command history globally.

2020: $ history | cut -c 8- | grep '^git ' | sort | uniq -c | sort -n | tail

2023: $ cat ~/.bash_history | grep -o '^git \([^ ]*\( -[^ ]*\)*\|stash.*\)' \

| sort | uniq -c | sort -n

| Command | 2020 | 2023 | Command | 2020 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

git diff | 37 | 58 | git pull | 5 | 1 |

git grep | 51 | git fetch | 4 | 1 | |

git log | 28 | 24 | git rebase -i | 4 | |

git show | 25 | 19 | git checkout | 4 | |

git branch -v | 24 | 5 | git add | 4 | |

git status | 4 | 12 | git checkout -b | 3 | |

git commit -a | 7 | 6 | git stash drop | 2 | |

git commit --amend -a | 5 | 11 | git rm | 2 | |

git stash | 9 | git checkout -B | 1 | ||

git push | 5 | 2 | git branch -D | 1 | |

git stash pop | 6 | git blame | 1 | ||

git commit | 6 |

These numbers are smaller and noisier than I wish they were, but I think they adequately convey a point I’m trying to make:

you don’t need to know a lot of git commands to get the job done! You only need a

handful of commands, which you’ll use over and over.

Git’s map of history

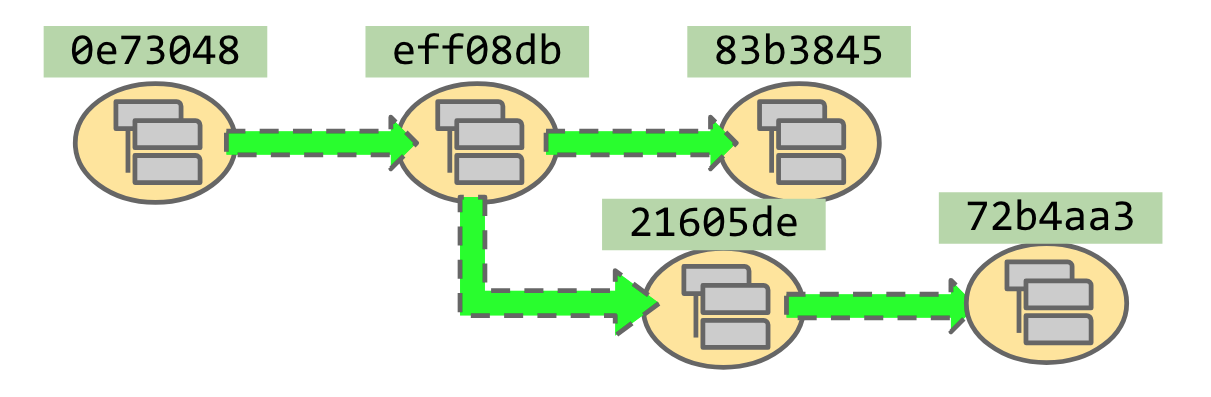

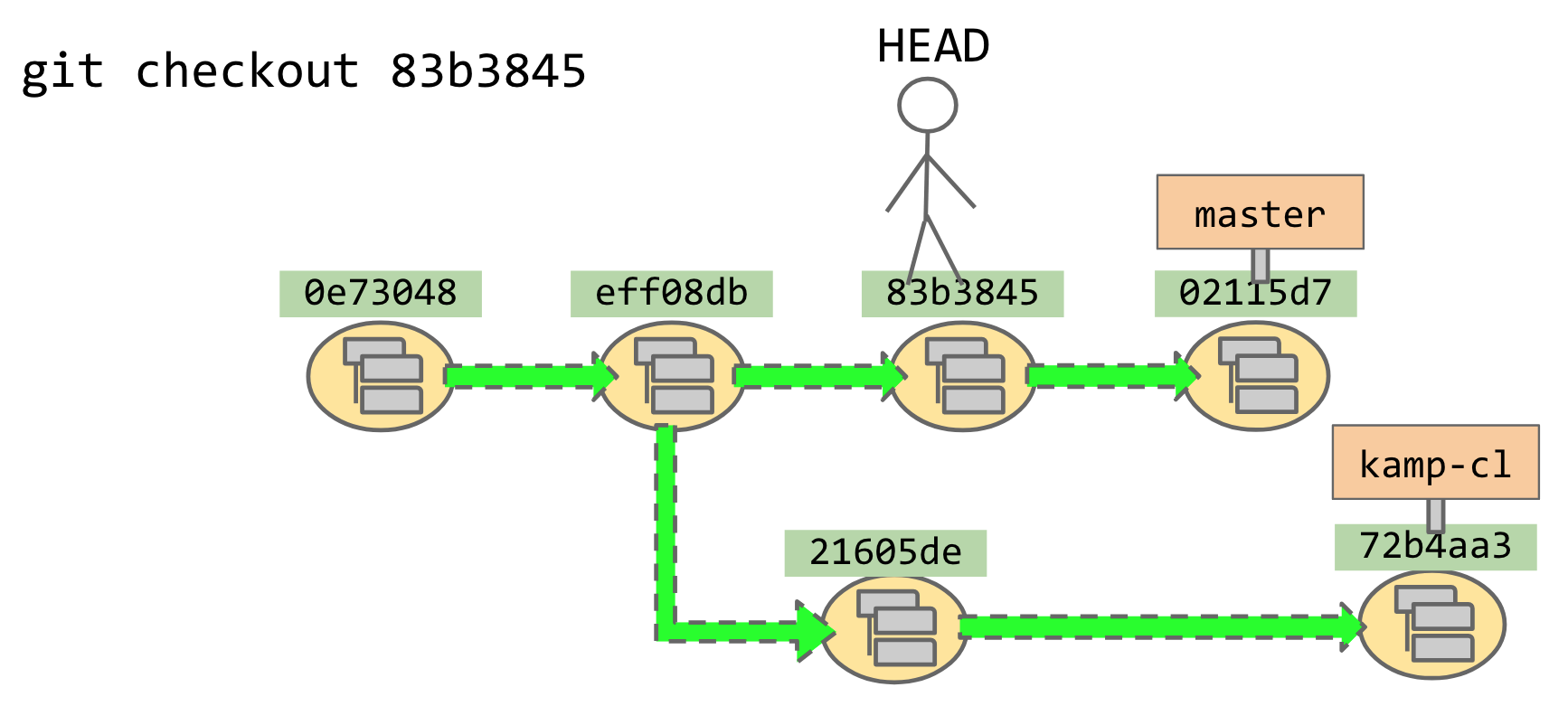

Git, as a version control system, manages not only the current version of your source code but also its entire history — all “past” and “future” versions too. So our codebase has a directory-and-file structure (represented here by the little pictogram of gray boxes), but in a higher dimension, orthogonal to the dimension of directories and subdirectories, Git maps out a bunch of “alternate-universe” ways that file structure could (or did at some point) look. In this image, the green arrow of time always points forward into the future, even though Git actually stores each node’s predecessor(s). (Git doesn’t store successors in that same efficient way; tracing a file forward into the future is harder than tracing it back into the past.)

Each node in the graph — each commit — is identified by a SHA hash, which is just a random-looking hex number.

These hashes are really 40 characters long, but Git can handle any shorter prefix as long as it’s

unambiguous. In practice, 7 characters are enough to avoid ambiguity; use 10 if you’re really paranoid.

We can navigate the history graph using only these hashes (git checkout eff08db,

git diff 0e73048..21605de), but that’s not very user-friendly. So Git provides the notion of

branches, which we can think of as signposts that help us navigate the wilderness of SHA hashes.

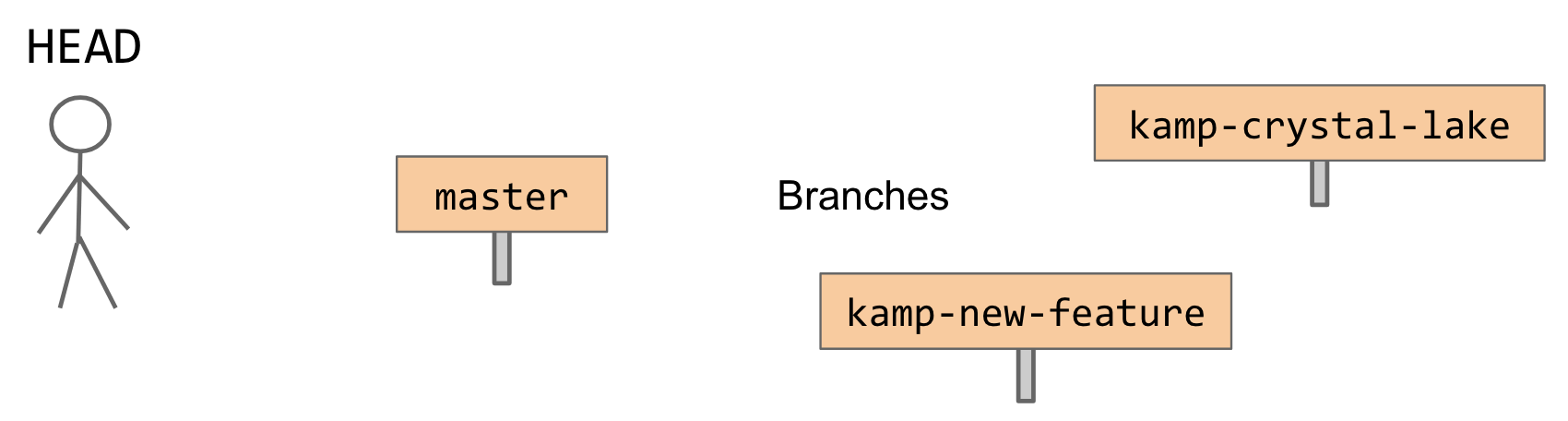

We also have that little dude labeled HEAD. HEAD is not a branch; it’s a special label for

“where am I in history (what commit do I have checked out) right now.” That is, our little dude

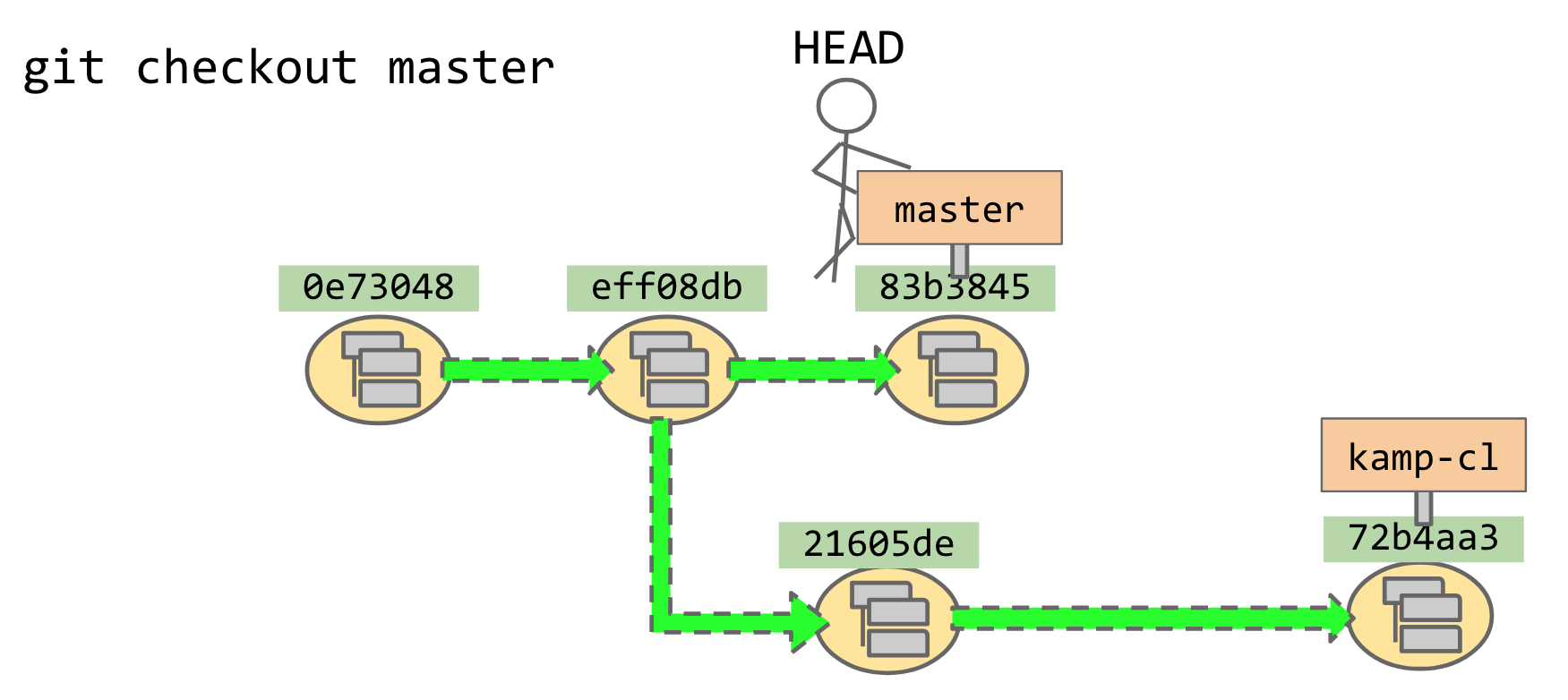

is not a signpost. But if I git checkout master — “Dude, go to the signpost labeled master” —

then my little dude will go and grab onto that signpost.

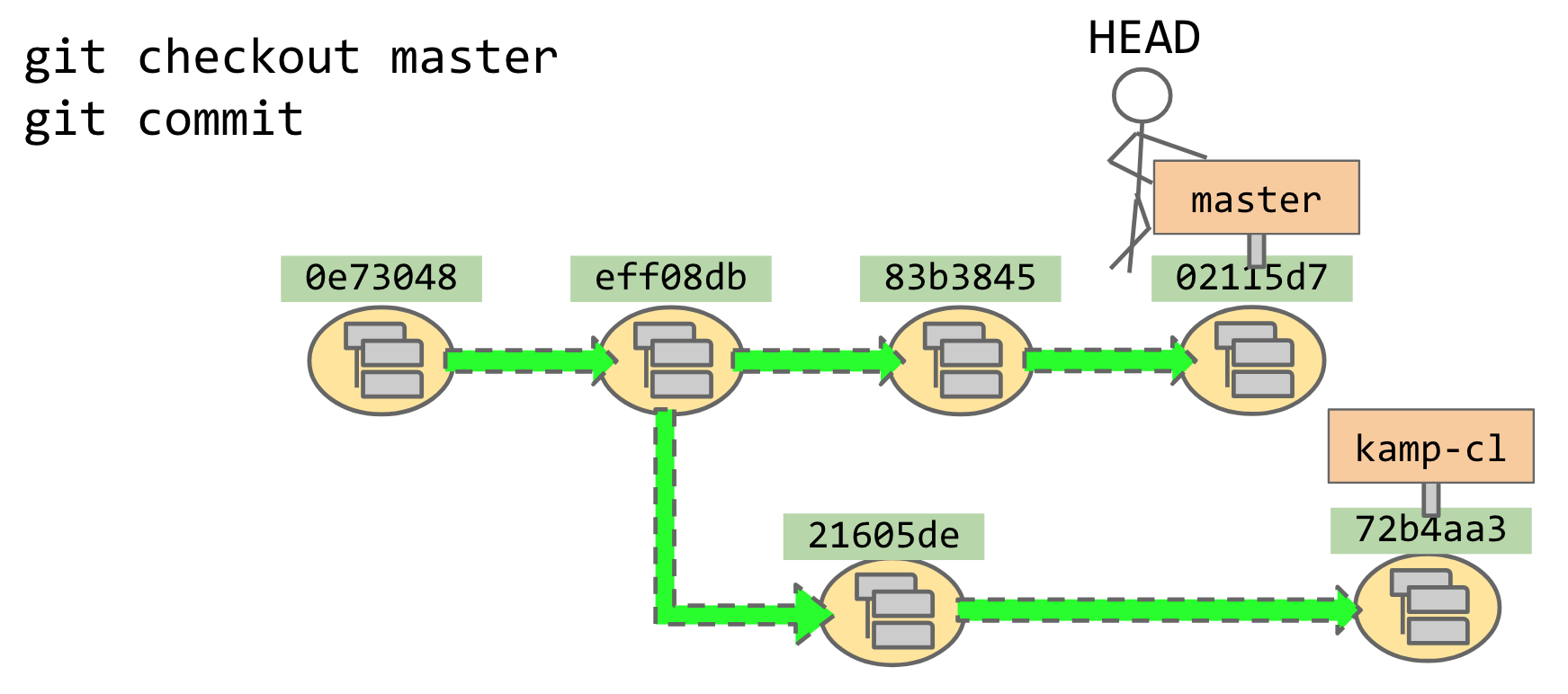

If I edit a file in my codebase — say, edit foo.cpp; git add foo.cpp — and then git commit,

that will cause a new node to appear in the graph. The new node will have its own unique SHA hash,

my little dude will have moved to it, and, most importantly, he’ll have brought the master

signpost with him! Now master labels the node we just committed.

I can also git checkout 83b3845 directly. Since I didn’t name a signpost, my little dude

isn’t holding onto anything.

This is known as “detached HEAD” state. I can bum around in

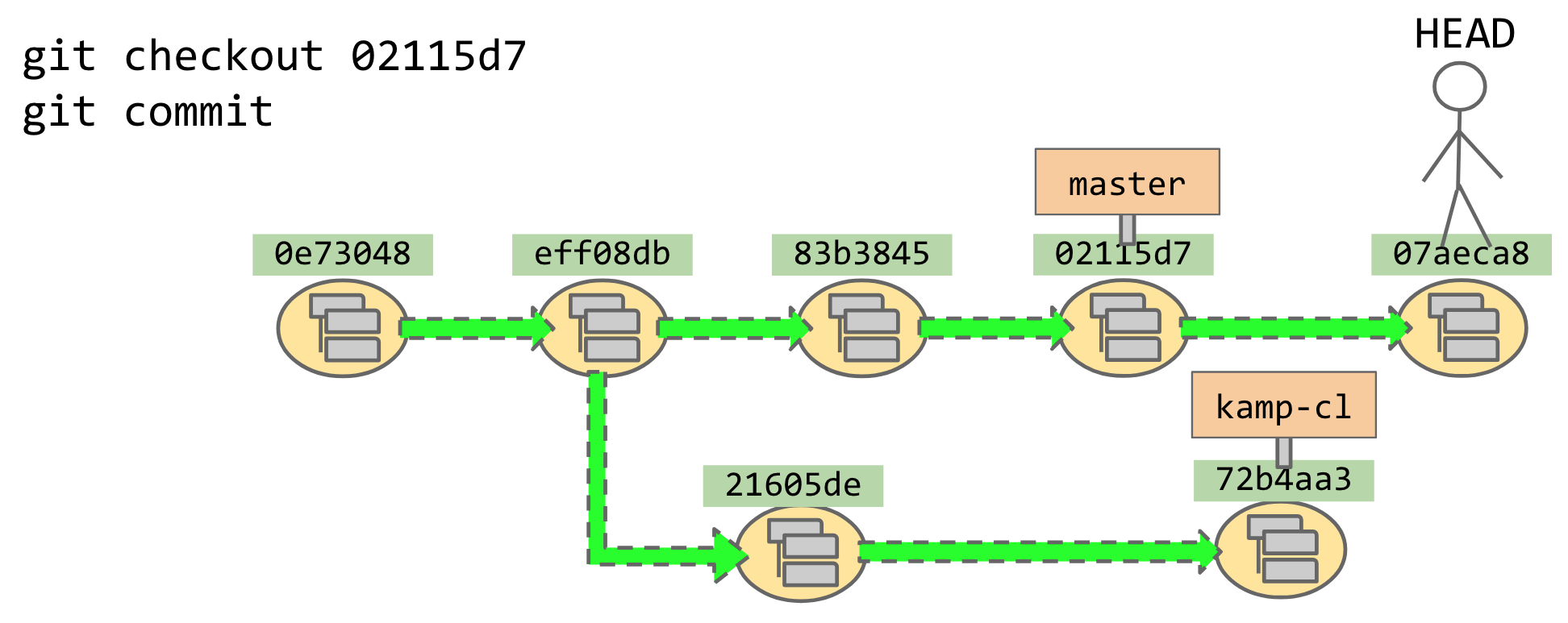

“detached HEAD” state if I want. I can even revisit the-commit-also-known-as-master by

saying git checkout 02115d7; that’ll put me at that node but not holding onto the signpost,

so that when I make another change and git commit, the signpost won’t come with me.

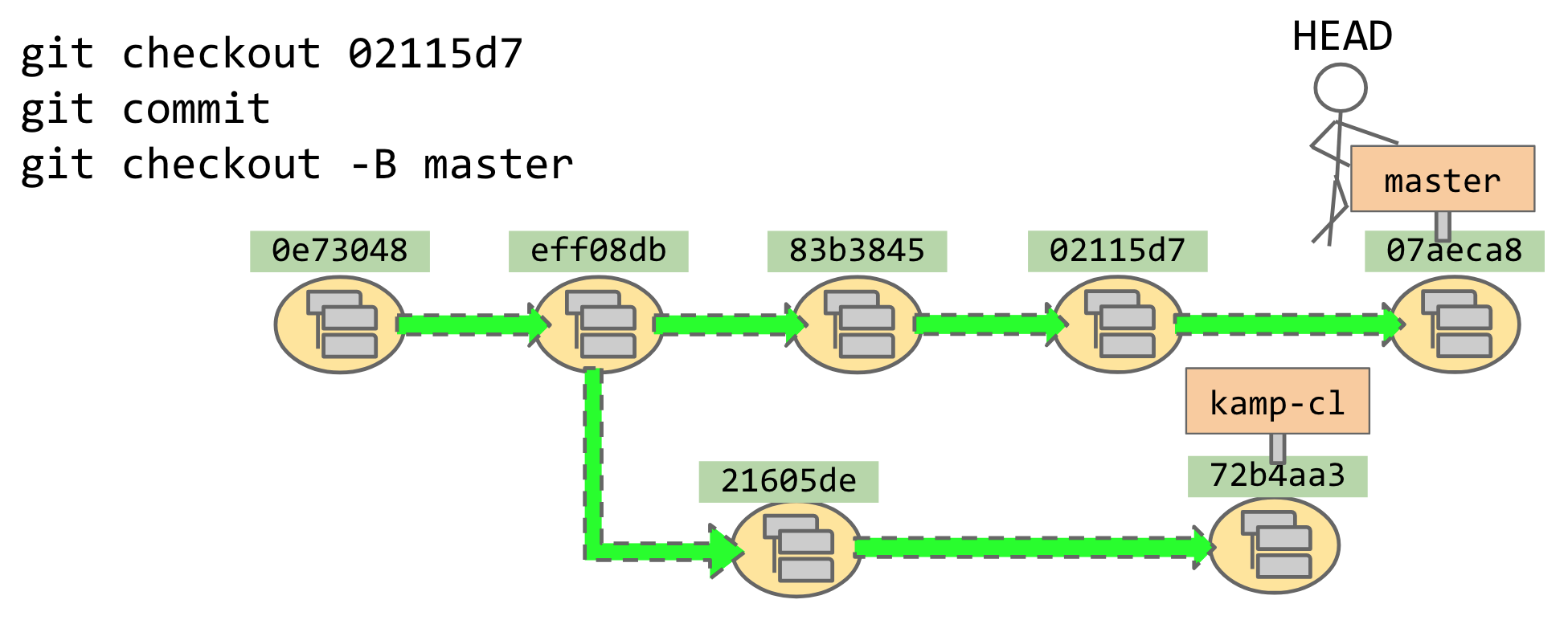

I can — if I want — do a lot of work in “detached HEAD” state, and only afterward decide that

I’d like to mark this branch with a signpost. The command for that is git checkout -B <branchname>,

which I think of as “Accio signpost!”

This illustrates something about git that’s both a pro and a con: The same “top-level” command

can mean vastly different things depending on its exact arguments.

git checkout 1234567means “move HEAD to1234567in detached-HEAD state.”git checkout mastermeans “move HEAD tomasterand grab onto that signpost.”git checkout -B mastermeans “make a signpost formasterright here at HEAD (or move it to here, if it already exists somewhere else).”git checkout -b mastermeans “make a signpost formasterright here at HEAD (or error out, if it already exists).”

At least all of those command lines have to do with “moving” something — either moving our little dude

around the map, or moving a signpost to our little dude. But git checkout can also mean messing with

our file structure (our working tree) without touching the map at all!

git checkout 1234567 -- foo.cppmeans “give me a copy offoo.cppas it looks in commit1234567, overwriting whatever’s there in my current checkout.”

Know the equivalents of ls

When you’re playing a text adventure, you end up typing LOOK a lot. When navigating around

a directory hierarchy, you probably do a lot of ls, ls -lAF, and pwd. When navigating

around in Git, you’ll use these four commands a lot:

git branch -v displays the branch names and tippy-top commits for each branch of your local repo.

So it’s kind of like ls — “show me all the things I’ve got going on right now.”

It also puts a star next to the branch that you’re currently on, so it’s also kind of like pwd or whoami —

“What am I working on right now, again?”

It also can tell you when any of your branches are

[ahead 1] or [behind 3] compared to their upstream counterparts, if you’ve set them

up to track a particular remote branch.

You will invariably type

git branch vat some point. That meansgit checkout -b v, except that it doesn’t set HEAD to grab ontovautomatically. Congratulations, now you have a branch namedvin your local repo. To delete that branch, typegit branch -D v.

git log shows the history of your current HEAD.

git diff displays the diff between your working tree and your currently-checked-out HEAD.

It’s like, “What unsaved work would I lose if I switched to a different branch right now?”

Okay, technically

git diffshows only unstaged work — changes since the last time yougit add’ed the relevant file. To see all uncommitted work — changes since the last time yougit commit’ed the file — you’d usegit diff HEAD. I don’t spend much time with staged-but-uncommitted diffs, so the difference between these two commands isn’t a core part of my personal mental model.

git show displays the diff between your HEAD commit and the previous commit.

It’s inordinately important to me because I tend to commit things locally as I work on them,

and then repeatedly weigh the pros and cons of git commit --amend -a (squashing my working tree into

the previous commit) versus git commit -a (creating a new commit with just the stuff I’ve

done since the last time I committed). So I might do a quick git show to remind myself what’s

currently at the top of the tree, followed by a quick git diff to see whether what I’ve just

done would mesh well with it or whether it merits a completely separate commit.

These commands can also be used with arguments; read on.

Know how to search the git history

You can use git log 21605de to see the history of that specific named commit;

git diff eff08db..master to diff any two commits against each other;

and git show eff08db to view a specific commit’s changes.

Each of these commands can also take any number of file or directory paths (after a --

if necessary to disambiguate between a path and the name of a branch or commit).

Use git log 21605de -- foo/bar.cpp to see the history of changes affecting the

named file(s) or path(s), along the history of the named commit;

git diff eff08db..master -- foo/ to diff any two commits against each other (like diff -r oldfoo/ newfoo/),

and git show eff08db -- foo/ to view a specific commit’s changes to the contents of foo/.

git grep 'reg\(ular \)*ex' 21605de -- foo/ greps the named files or directories for that regex,

a lot like grep -r, except that it’ll skip any file not tracked by Git (including the .git/

bookkeeping directory itself). Omit the commit hash to grep the working tree (this is the 99% case).

Omit the path argument(s) to recursively grep only your current working directory.

For me that’s usually the CMake build directory, which contains nothing tracked by Git.

So usually I’m doing, like, git grep 'inline constexpr' ../libcxx/. (The -- between the commit hash

and the path(s)

git blame -- foo/bar.cpp displays a single file (like less foo/bar.cpp), but showing

in the left margin the SHA hash of the last commit that modified each line. I often use this

to track down the patch that introduced a bug, by alternating between git blame and git show —

git blame file.cpp to find the commit hash a1b2c3d that last changed the bug’s vicinity;

git show a1b2c3d file.cpp to see if that commit is the culprit; and if not, git blame a1b2c3d~ file.cpp

to find the commit that changed the bug’s vicinity before that. (In Git, whenever xyz identifies a

commit, then xyz~ identifies that commit’s predecessor. So HEAD~ is the commit before HEAD; master~

is the commit before master; and so on.)

Know how to work with patches

If you have local uncommitted changes you just want to throw away forever, you can do

git stash; git stash drop. The usual use of git stash is as a “clipboard” to hold changes

temporarily (e.g. while you switch branches); reapply the stashed changes with git stash pop. But

I more often use it as a quick way to restore the working tree to its pristine state. (Well, almost

pristine. Untracked files won’t be messed with.)

To split up a patch into two smaller patches, I’ll often use git revert and git rebase.

(I never, ever use rebase without -i!) Try following along with this example:

$ cd /tmp

$ git init foobar

$ cd foobar

$ cat >test.cpp <<EOF

int main() {

puts("hello world!");

return 0;

}

EOF

$ git add test.cpp

$ git commit -a -m "Initial commit"

(By the way, in real life I never use -m; I’m using it here just to keep the example short.)

Now let’s fix two issues with the code, but (in our exuberance) do them both in the same commit:

$ cat >test.cpp <<EOF

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

puts("hello world!");

}

EOF

$ git commit -a -m "Combined patch"

Now your Git history should look something like this:

$ git log --oneline

9bd8138 (HEAD -> main) Combined patch

af97aea Initial commit

To separate out the first diff (adding #include) from the second diff (removing return),

I’d continue with these commands:

$ git revert HEAD

$ cat >test.cpp <<EOF

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

puts("hello world!");

return 0;

}

EOF

$ git commit -a -m "Add include"

$ git rebase -i HEAD~~~

Your editor will come up with a summary of the last three commits — that is,

the half-open range from (but not including) HEAD~~~ up to (and including) HEAD.

It’ll look something like this:

pick 9bd8138 Combined patch

pick 23a3033 Revert "Combined patch"

pick cc610eb Add include

followed by some helpful documentation explaining that pick means “take this commit,” but

you can change it to e for “stop and let me (e)dit the files at this point,” or

r for “take but (r)eword the commit message,” or

s for “take and (s)quash into the previous commit,” or

f for “squash into the previous commit as a trivial (f)ixup that doesn’t even require rewording the first commit message.”

Swap around those lines so that they look like this:

pick cc610eb Add include

r 9bd8138 Combined patch

This means “First, add the #include; then, continue by applying the combined patch (half

of which we’ll have already applied by this point), and let me reword the commit message for

that patch since now it’ll just be the second half.”

Then save-and-exit the editor; and when it opens again, change the commit message from

“Combined patch” to “Remove return.” When the rebase is finished, your history should look

like this:

$ git log --oneline

21455a0 (HEAD -> main) Remove return

17c883a Add include

af97aea Initial commit

and git show 21455a0 should show just one removed line.

Now let’s combine those two patches back into one! The easy way to do this is with a rebase-and-squash:

$ git checkout -b easy-way

$ git rebase -i HEAD~~

Alter the contents of the editor window from

pick 17c883a Add include

pick 21455a0 Remove return

to

pick 17c883a Add include

s 21455a0 Remove return

and save-and-exit. Then, when the editor opens again, change the multi-line commit message to “Combined patch (easy)”. (Alternatively, instead of pick-and-squash, you could have used reword-and-fixup.)

$ git log --oneline

6845933 (HEAD -> easy-way) Combined patch (easy)

af97aea Initial commit

Alternatively, we could combine the two patches the hard way.

(I mean, it’s not that hard; but it’s more manual.) First we navigate our

little dude named HEAD to where we want our new trail of commits to begin; then we’ll

accio a signpost named hard-way; then we’ll use git checkout <commit> -- <paths>

to make our working tree look like we want it to look; and finally we’ll commit that

diff.

$ git checkout master

$ git log --oneline

21455a0 (HEAD -> main) Remove return

17c883a Add include

af97aea Initial commit

$ git checkout af97aea

$ git checkout -b hard-way

$ git checkout main -- test.cpp

$ git status

On branch hard-way

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

modified: test.cpp

(Git is reminding you that it can be fiddly to get rid of unwanted changes to tracked files, especially once they’re

“staged” via git add; or via git checkout --, which stages its diffs automatically. Git recommends git restore

for this; but if I decide I don’t want the changes after all, I’ll more likely throw them away wholesale with git stash; git stash drop.)

We continue, using git diff HEAD -- to show the diff between HEAD (our previous commit) and our current working tree:

$ git diff HEAD --

(shows that test.cpp now appears the same as it did in main)

$ git commit -m "Combined patch"

$ git log --oneline

999461a (HEAD -> hard-way) Combined patch

af97aea Initial commit

$ git diff easy-way hard-way

(no output, because the contents of the two branches are identical)

To cherry-pick a patch from someone else’s repo,

update your .git/config to include a definition of their repo as a “remote.”

(Git has built-in commands starting with git remote for doing this kind of thing,

but I don’t bother. It’s faster to edit the config file by hand.)

[remote "Quuxplusone"]

url = git@github.com:Quuxplusone/llvm-project

fetch = +refs/heads/*:refs/remotes/Quuxplusone/*

Fetch the contents of the remote down to your own local repository. This will create

tracking branches with names like Quuxplusone/main, Quuxplusone/trivially-relocatable,

et cetera. These aren’t quite “real” branches, and won’t appear in git branch -v by default;

but they’ll appear in git branch -rv (-r for “remote”).

Then, use git cherry-pick to apply any single commit to your current HEAD.

$ git fetch Quuxplusone

$ git branch -rv | grep example-feature

Quuxplusone/example-feature 1a2b3cd [clang] Add something, for example

$ git log Quuxplusone/example-feature

$ git checkout main

$ git checkout -b my-own-new-feature-branch

$ git cherry-pick 1a2b3cd

$ git log

If you’re cherry-picking at work (e.g. cherry-picking a bugfix from master into a release branch),

you’ll want to use git cherry-pick -x 1a2b3cd, which will automatically append a

little “(cherry picked from commit 1a2b3cd87ab65de…)” tagline to the commit message.

Notice that the cherry-picked commit will show up with its original author and date.

Git separately tracks both the author of a patch and the committer, so you’ll be listed

as the committer but not the author. Normally only the author is displayed by git log.

To see both author and committer, run git log --format=fuller. To set yourself as the author

of a cherry-picked commit, run

$ git cherry-pick Quuxplusone/example-feature

$ git commit --amend --reset-author

Lagniappe

There’s a lot more I could say about Git (see that slide deck), but I think this post is long enough already,

and we’ve covered what I consider to be the basic muscle-memory commands. There’s one more command that’s

useful specifically if you’re working on the llvm-project codebase;

that’s git-clang-format. Their CI will complain when a patch adds code that doesn’t match

the project’s .clang-format style. But if you run clang-format -i test.cpp, it’ll format the entire

file — not just the tiny part you’re trying to patch! That creates extraneous diffs that irk reviewers.

The right way to format just your tiny diff is to use git-clang-format:

$ git commit -a -m "My original commit"

$ git-clang-format HEAD~ --

changed files:

test.cpp

$ git diff

$ git commit -a --amend -m "My original commit, formatted"

See also:

- “git: fetch and merge, don’t pull” (Mark Longair, April 2009)

- “How to Write a Git Commit Message” (Chris Beams, August 2014)

- “git rebase: what can go wrong?” (Julia Evans, November 2023)