Both sides of the shield

From John Cooper Mendenhall’s “Aureate Terms” (1919):

Who dare call the clerks blind who saw only the golden side of the shield?

This is a reference to a fable originating in Beaumont’s Moralities (1753). There it is titled “The Parti-Colored Shield”:

In the Days of Knight-Errantry and Paganism, one of our old British Princes set up a Statue to the Goddess of Victory, in a Point where four Roads met together. In her right Hand she held a Spear; and rested with her left upon a Shield. The Outside of this Shield was of Gold, and the Inside of Silver. On the former was inscribed, in the old British Language, “To the Goddess ever favourable”; and on the other, “For four Victories obtained successively over the Picts, and other Inhabitants of the Northern Islands.”

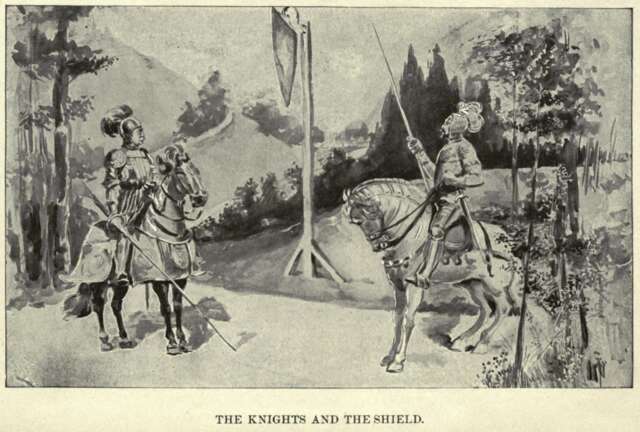

It happened one Day, that two Knights completely armed, the one in black Armor, and the other in white, arrived from opposite Parts of the Country, at this Statue, just about the same Time; and as neither of them had seen it before, they stopped to read the Inscriptions, and observe the Excellence of its Workmanship. After contemplating it for some time, “This Golden Shield,” (says the Black Knight,)— “Golden Shield!” cried the White Knight (who was as strictly observing the opposite Side) —”why, if I have any Eyes, ’tis Silver!” “I know nothing of your Eyes,” replied the Black Knight; but if ever I saw a Golden Shield in my Life, this is one.” “Yes,” returned the White Knight, smiling, “’tis very probable indeed, that they should expose a Shield of Gold in so public a Place as this is! For my Part, I wonder that even a Silver one is not too strong a Temptation for the Devotion of some of the People that pass this Way; and it appears by the Date, that this has been here above three Years.” The Black Knight could not bear the Smile with which this was delivered, and grew so warm in the Dispute, that it soon ended in a Challenge. They both therefore turned their Horses, and rode back so far, as to have sufficient Space for their Career; then fixed their Spears in their Rests, and flew at each other with the greatest Fury and Impetuosity. Their Shock was so rude, and the Blow on each Side so effectual, that they both fell to the Ground so much wounded and bruised that they lay there for some time, as in a Trance.

A good Druid, who was travelling that Way, found them in this Condition. The Druids were the Physicians of those Times, as well as the Priests. He had a sovereign Balsam about him, which he had composed himself (for he was very knowing in all the Plants that grew in the Fields, or in the Forests). He staunched their Blood, applied his Balm to their Wounds, and brought them, as it were, from Death to Life again. As soon as he found them sufficiently recovered, he began to enquire into the Occasion of their Quarrel. “Why, this Man,” cried the Black Knight, “will have it that that Shield yonder is Silver.” —”And he will have it,” replied the White Knight, that it is Gold”;— and then told him all the Particulars of the Affair. “Ah,” says the Druid, with a Sigh, “you are both of you, my Brethren, in the right; and both of you in the wrong! Had either of you given himself Time to look upon the opposite Part of the Shield, as well as that which first presented itself to his View, all this Passion and Bloodshed might have been avoided.” However, there is a very good Lesson to be learned from the Evils that have befallen you on this Occasion. Permit me therefore to entreat you, by all our Gods! and by this Goddess of Victory in particular! never to enter into any Dispute for the future, till you have fairly considered each Side of the Question.”

The story was set to verse by Mary Fisher (1807–?) in a poem titled “Both Sides of the Shield.” Fisher’s poem, published 1859, concerns a dispute between “the Dean of Carlisle, Dr. Francis Close, and the Precentor of the Cathedral, Mr. [Thomas Gott] Livingstone.”

I’m oft reminded of a tale in youth,

(When ev’ry tale we heard or read seem’d truth)

‘Twas of two knights who once upon a day,

Armed “cap-a-pied” met on the king’s highway.

Between them stood a shield (strange to behold),

One side was silver, t’other burnished gold:

Men were more honest in those days, I ween,

At least such shield would now not long be seen.

It even then created some surprise,

For one cried out— “Can I believe my eyes?

A shield of gold in such a place as this!”

“You well may doubt them, for they see amiss,”

Replies the other: “To my mind ’tis clear

They’re not too wise that leave e’en silver here!”

We need not tell how each maintained his side—

How anger rose, and how at length they ride

Full tilt against each other; then too late,

Unhorsed and wounded they lament their fate;

For having pass’d the object of the fray,

They see too clearly where their error lay,

And vow in future ere they take the field,

To well examine both sides of the shield.Now to our Moral. Have ye not all been

A little hard upon your friend, the Dean?

That there were faults on both sides, there’s no doubt,

What quarrel ever lasted long without?

But had the facts been known, ’tis very clear,

Your judgment on him had been less severe.

We trust at last all bickering may cease,

Within the church of God there should be peace;

Such petty squabbles are a sad disgrace,

And never should be heard in such a place;

For when their Master came on earth to live,

His earliest, latest lesson, was— Forgive.

And we have learned a lesson to suspend

All hasty judgment, till we know the end;

To hear two parties ere we credence yield,

And well examine— Both sides of the Shield.

The fable was a favorite of Baptist preacher Charles Haddon Spurgeon. For example:

You have heard of the two travelers who met opposite the statue of Minerva, and one of them remarked, “What a glorious golden shield Minerva has!” The other said, “Nay, but it is bronze.” They argued with one another, they drew their swords, they slew each other; and, as they fell, dying, they each looked up, and the one who said the shield was made of bronze discovered that it had a golden side to it, and the other, who was so bold in affirming that it was gold, found that it had a bronze side too. The shield was made of two different metals, and the combatants had not either of them seen both sides. (“#2976: Order is Heaven’s First Law,” 1906)

They are like the men who quarrelled as to the material of which a certain shield was made. One of them said that it was a golden shield; the other was equally sure that it was a silver one: whereas it so happened that it was gold on one side and silver on the other. So they fiercely wrangled when they might very well have been agreed if they had known a little more. (“#2233: Both Sides of the Shield,” 1891)

And more: “Oh, what matchless beauties are combined in our blessed Savior! You may look on this side of the shield, and you will perceive that it is of pure gold. Then you may look on the other side of it, but you will not discover that it is brass, as in the fable, for it is gold all through” (#2769, 1881) — “Brethren, be willing to see both sides of the shield of truth” (#979, 1871).

Charlotte Yonge published a two-volume novel titled The Two Sides of the Shield (1885).

We find in the Andover Townsman of May 8, 1891, a letter to the editor headlined “Two Sides of the Shield.”

An even further embellished version of the two-knights story appears in Trumbull White’s Silver and Gold, or, Both Sides of the Shield (1895), a collection of American writings on bimetallism:

Once upon a time, so the legend runs, a shield hung at the side of a highway, along which knights were wont to journey as they rode to tourneys and to jousting-meets. It was so swung from its support that one side of the shield looked down the highway to the east, and the other side, as would naturally be the case, looked westward. On a certain fair morning in spring, as the sun was rising over the eastern hills, two knights armed cap-à-pié, with lances in rest and visors raised, came near to one another down the road. One of the knights was dressed in chain armor of silver links, and was mounted on a beautiful white charger, which seemed to share his rider’s spirit and bravery. The other knight was clothed in gold mail, and proudly sat upon a fiery steed of ruddy chestnut hue, almost golden in its brightness. […]

“Good morrow, sir knight,” said the one of gold, “it is a fair and bright morning while we ride. When ye pass to this side of the swinging shield, fail not to turn and look how yonder sun reflects from its golden face, and dazzles the inquisitive eye that would read its scription and admire its skilful carving. A stranger knight am I to this highway. Can ye tell to me the reason why the shield hangs here?”

“By my halidome,” quoth the other, “I cannot tell, most courteous knight, why hangs the shield. But sure am I your eyes do play you treason in the sunlight’s glare. For silver is it, silver as my armor here […]”

[…] They fought throughout the quiet afternoon, beneath that swinging shield above their heads. And when the sun was sinking in the west, illuming now the other shining side, both fell there in the highway where they fought, wounded, exhausted, spent of blood, and dying. As these two knights had met in battle shock, they wavered forward now and then drew back, crossing the line that marked the shield’s position, and shifting often each his own attack. So when they fell, it happened that the knight of gold was lying farther to the west, and he of silver on the eastern side. And each knight raised his eyes to see the shield whose metal face had forced him to a fight. Then he of silver cried aloud, amazed, “What do I see? A shield of gold it is.” And he of gold in wonderment replied, “Now silver is it, or I am deceived.”

Then struggled they from where they fallen were, despite their wounds, their weakness, and their pride, each to his former point of view again. And when they realized what was the truth, they lifted up their voices loud and wept, that such a fight should be, and such a fate, for gallant knights to face when both were right in part and both were wrong. Then talked they of their early lives, and found by strange adventure that they two were brothers. One mother had they, but their lives had been apart from early childhood, and their paths had spread until they met again on this sad day.

The shield that hung above their knightly heads, as hand in hand they waited thus, and died, was golden on the side that faced the east. The western side was silver.

Finally, Ambassador Archibald Butt wrote a novel titled Both Sides of the Shield (published posthumously in 1912, after Butt went down with the Titanic).

I wasn’t the first to wonder the source of this story. From Notes & Queries (1880-02-14), the Rev. Edward Marshall of Sandford St Martin inquires:

“The gold and silver shield.”—Lord Granville is reported to have said, in his speech at the opening of Parliament, “Unlike the old knight, he sees both the silver and the golden side of the shield.” I take the opportunity to ask whether any correspondent of “N. & Q.” can refer to the origin of the story here alluded to. The question was asked some time since [i.e. on 1875-10-30], and obtained no reply.

The following week (1880-02-21) William Platt of Piccadilly provided the answer:

“The gold and silver shield” (6th S. i. 137).—The story of “the party-coloured shield,” selected from Beaumont’s Moralities, was reprinted in a collection of Useful and Entertaining Passages in Prose (pp. 92–4), and published at Paris in 1826 by G. Hamonière.

The editor of Notes & Queries expresses further puzzlement as to the identity of this “Beaumont”; but in fact “Sir Harry Beaumont” was a pen name of Joseph Spence (1699–1768).