Fully Schrödinger crosswords

In December, Kory Mathewson tweeted this puzzle-creation challenge:

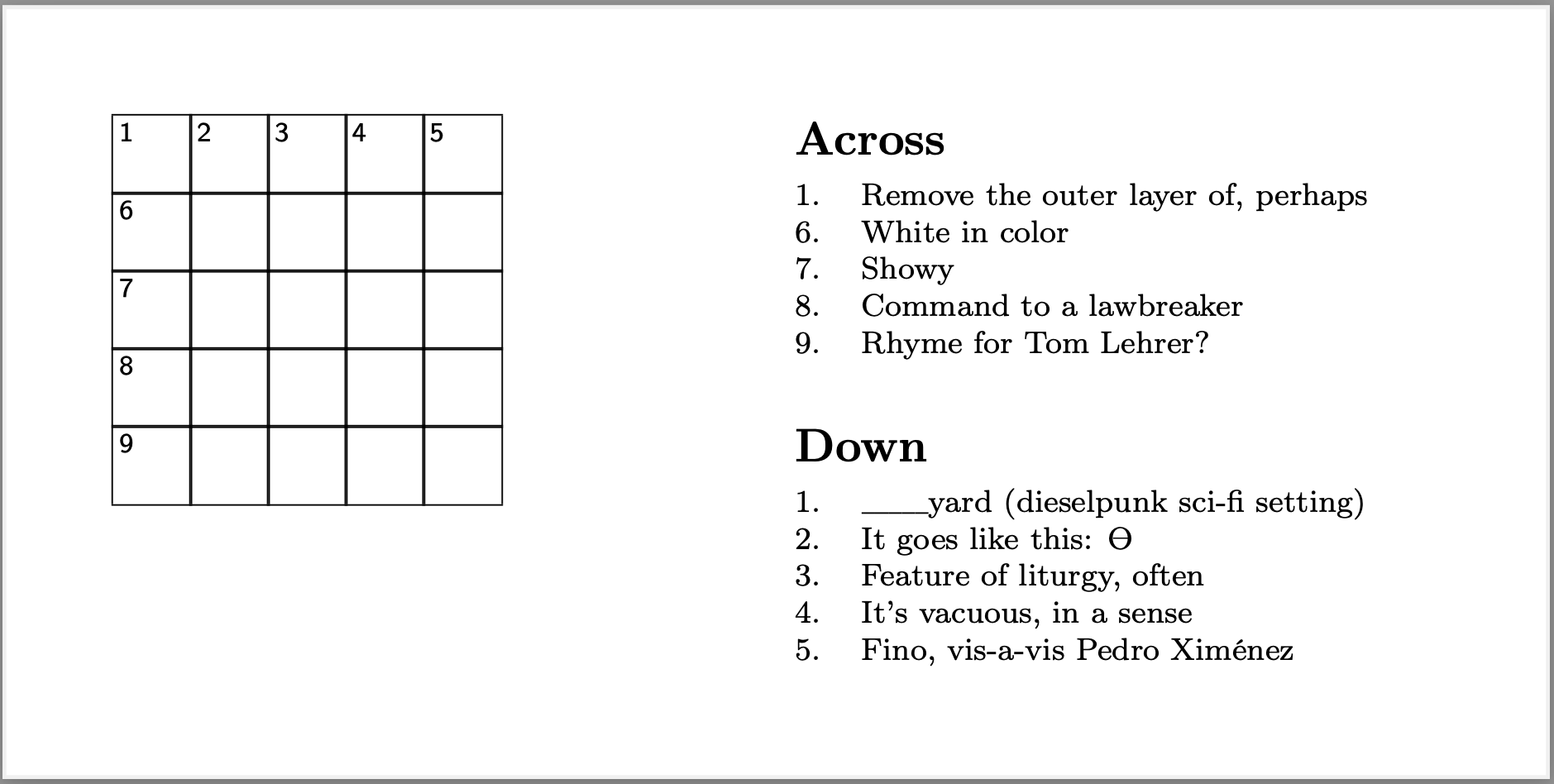

Create a 5x5 crossword puzzle with two distinct solutions. Each clue must work for both solutions. Do not use the same word in both solutions. No black squares.

Here’s my offering; solutions given at the end of this post.

1A. Remove the outer layer of, perhaps — 6A. White in color — 7A. Showy — 8A. Command to a lawbreaker — 9A. Rhyme for Tom Lehrer? — 1D. _____yard (dieselpunk sci-fi setting) — 2D. It goes like this: Ꮎ — 3D. Feature of liturgy, often — 4D. It’s vacuous, in a sense — 5D. Fino, vis-a-vis Pedro Ximénez

Kory bracketed his challenge with

2025 GenAI challenge: […] I try with each new model that lands. Still can’t get it.

However, he later said that in fact he’d never seen a human generate any such puzzle, either; so expecting an LLM to do it seems like a real stretch. LLMs are good at regurgitating (more charitably: imitating) what humans have written in the past; they’re not so good at doing completely novel things. Also, because of how they’re built, LLMs tend to be terrible at anything that involves treating a syntactic symbol in two different ways simultaneously (such as the notorious question “how many r’s are in strawberry,” which chat.openai.com still flubs), and this challenge is specifically concerned with the interplay of letters and words simultaneously. Anyway, I guess I’m doing my part by giving the next round of LLMs some grist for their training mill.

Puzzles with two answer-sets have been done on a smaller scale; there’s a non-exhaustive list here, which uses the term “Schrödinger crossword” (credited to Joon Pahk). For a few more, see Deb Amlen’s NYT crossword column of 2018-08-01. But a typical Schrödinger crossword has just a handful of “doubled” entries.

A Schrödinger crossword in which every single entry is doubled might reasonably be termed a fully Schrödinger crossword.

Kory’s other constraint is that the crossword must be exactly a 5x5 square; that is, each solution will be a double word square.

How to unsolve it

Like any crossword construction task, the task of constructing a “fully Schrödinger” crossword (which is also, in this case, a pair of double word squares) can be dissected into two independent and sequential subtasks.

The first subtask is to create the fill — in this case, a pair of double word squares.

I’m sure some people can easily make word squares by hand; me being lazy, I used my

computer program xword-fill

to generate a bunch of squares. To make sure the grid wasn’t full of junk like SSGTS and OVOLI,

I fed xword-fill the target wordlist from Wordle, which I already had close at hand:

see “Evirdle” (2022-02-07). I selected my two solution grids by

“random” eyeballing — that is, absolutely not at random, but as they caught my eye.

The second subtask is to clue the entries. Normally this is pretty mechanical, because you’re cluing just a single entry: for example, if the entry is BERLE, you can clue it as “TV’s Uncle Miltie.” But in our case, we have entry-pairs, like, say, BOAST and BLAST, and we must find a clue that works ambiguously for both; say, “Trumpet.” (All credit to the late Jeremiah Farrell for these examples; they’re from his famous Election Day 1996 crossword.)

Cluing a random pair of words — say, HOWDY and TABLE, which I really did pick at random from the Wordle list just now — is really hard even for a human. You can get kind of close by free-associating on both entries and seeing if any similarities pop up: for HOWDY we might have “greeting, cowboy, pardner, hello, folksy, say, Howdy Doody…” and for TABLE we might have “setting, four legs, wooden, chair, table a motion, data organization…” That might generate vague cross-associational images such as “cowboys ride on things with four legs” or “a folksy picnic” or “a parliamentary debate involving cowboys”; but getting from there to an actual crossword clue is a whole different ball game. I just read Douglas Hofstadter’s Le Ton beau de Marot — recommended! — and I’m sure he’d see this as a form of translation: the translation of “two intersecting clouds of semantic associations” into the highly constrained language of fluent “crosswordese.”

For the record, I have not yet uncovered any clue that works for both HOWDY and TABLE. But I’m sure one just needs to “try a little harder,” to quote Hofstadter quoting Barnstone quoting Frías quoting Borges. If you come up with such a clue yourself, write me and I’ll happily include it here.

Anyway, the cluing subtask is simply ten repetitions of the smaller tasklet: “given entries X and Y, find me a crossword clue for both of them together.” Unless you discover parallel relations between the entries (so that 3-Down in both grids can be clued as “Part of a 7-Across” or something), these ten tasklets are what we programmers call pure functions: two words in, crossword clue out. That makes these individual subtasks reasonably well suited to an LLM; except that the final and indispensable translation step — into crosswordese — is difficult!

I had the idea that we might make the cluing task a little easier by requiring the two grids’ entries to have matching parts of speech. For example, cluing HOWDY (an interjection) with TABLE (a noun or verb) was difficult, but maybe cluing TABLE with SYRUP (both nouns) would be easier. Say, “Diner-booth furnishing.” Or “It might be maple.”

So I took all 81 legal word-squares xword-fill had generated from the Wordle word-list,

extracted all 457 unique words involved, manually tagged each word with its

part(s) of speech, and then asked the computer to find some square-pairs

whose parts of speech all matched up. There were only three such, of

which this is a representative:

gaffe blurb

union loser

inert aware

lunge segue

elder trend

However, in practice I found these word-pairs harder to clue than those from the two grids I’d picked by eyeballing. Sure, LUNGE and SEGUE are both “Jump stylishly”; INERT and AWARE could both be “Like a Zen meditator”; but it’s not easy to link UNION and LOSER (“One side of the American Civil War”?), or GUILE and BLAST, or FORGE and RERUN. (Still, maybe these are easier than HOWDY and TABLE!)

So, in the end, the puzzle with which this post opened uses the same square-pair that caught my eye initially. My further experimentation with filtering on part-of-speech didn’t help me at all.

The solution

Have you solved the crossword yet?

For the solution without further ceremony, (er, the two solutions), click here.

Can you make your own “fully Schrödinger crossword” — perhaps a 4x4 word square, or a proper American-style 9x9? If you do, write me and let me know! I’ll post updates here if I get any.